CBD (cannabidiol), a component of cannabis, has gone from being a relatively obscure molecule to a worldwide healthcare craze, spawning billions in sales, millions of users, CBD workout clothing, pillowcases, hamburgers, ice cream — you name it. Concerns about such rapid adoption include the possibility that enthusiasm may be outweighing actual science, and that there are safety issues, such as drug interactions, that are being overlooked in the rush to treat chronic pain, insomnia, anxiety, and many of the other conditions that CBD is thought to help alleviate.

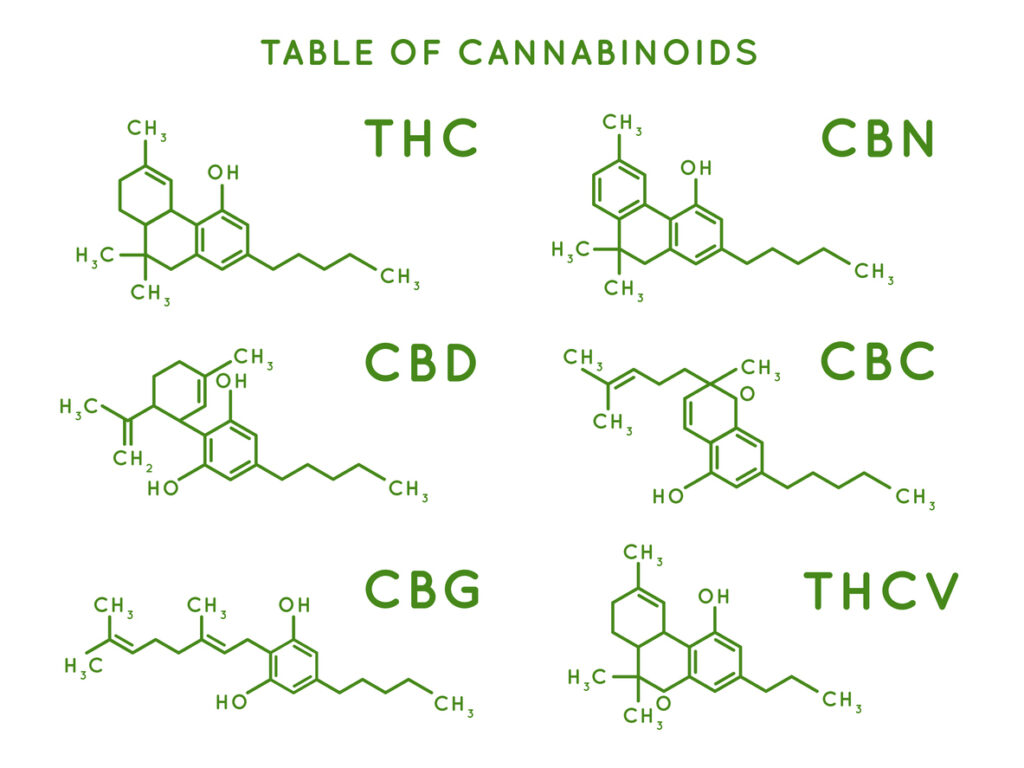

Cannabis, on the other hand, is made up of approximately 600 different molecules, 140 of which are known as cannabinoids because they work on our body’s endocannabinoid system — a vast network of chemical messengers and receptors that help control many of our most critical bodily systems, including appetite, inflammation, temperature, emotional processing, memory, and learning. New cannabinoids were bound to be discovered and commercialised sooner or later.

What are some of these newer cannabinoids, and what evidence suggests they might be beneficial?Unfortunately, because much of the data for these newly discovered compounds comes from animal studies, it will take some time and high-quality research to determine whether the benefits found in animals will apply to humans.

CBG, also known as cannabigerol, is a nonintoxicating cannabinoid that is being marketed for the treatment of anxiety, pain, infection, inflammation, nausea, and even cancer. It has a wide range of potential medical applications, but almost all of the research has been done on animals, making it difficult to extrapolate to humans. Experiments in mice have revealed that it can reduce inflammation associated with inflammatory bowel disease and slow the progression of colorectal cancer. It inhibits glioblastoma multiforme cells in cells (the type of brain cancer that Senator John McCain suffered from).

CBG has also been shown to be antimicrobial against a variety of agents, including the difficult-to-treat MRSA bug, which is responsible for a large number of hospital-acquired infections. CBG is also an appetite stimulant and may help with bladder contractions. The lack of regulation and standardisation that accompanies the entire supplement industry in this country means that you aren’t always guaranteed to get what you think you’re getting — and this is true for all of the substances discussed in this post.

CBN, or cannabinol, is found in trace amounts in the cannabis plant but is primarily a byproduct of THC degradation. Marijuana that has been sitting for too long has a reputation for turning into “sleepy old marijuana,” allegedly due to higher CBN concentrations, though there are other plausible explanations for this phenomenon. CBN is widely marketed for its sedative and sleep-inducing properties, but a review of the literature reveals that there is virtually no scientific evidence that CBN makes you sleepy, with the exception of one study of rats already on barbiturates who slept longer when CBN was added. This isn’t to say that CBN doesn’t make people sleepy, as many people claim; it just hasn’t been proven scientifically yet.

Usually, there is some evidence to back up claims about cannabinoids, at least in animal studies. CBN, on the other hand, has the potential (though only in animal studies so far) to act as an appetite stimulant and an anti-inflammatory agent, both of which would be extremely beneficial medical applications if they were to be realised in humans. A recent human study from Israel found that cannabis strains higher in CBN were associated with better symptom control of ADHD. More human studies are needed before marketing claims about the benefits of CBN can be supported by science.

THCV, or tetrahydrocannabivarin, has the potential to be exciting because it may aid in the treatment of our obesity and diabetes epidemics. Animal studies show that it lowers fasting insulin levels, promotes weight loss, and improves glycemic control. THCV was shown to significantly improve fasting glucose, pancreatic beta cell function (the cells that make insulin and eventually fail in diabetes) and several other diabetes-related hormones in a 2016 study published in Diabetes Care. It has been well tolerated in both animals and humans, with no significant side effects. Strains with high levels of cannabinoids such as THCV (and low levels of THC) are being cultivated in places such as Israel, where cannabinoid research is far more advanced than in the United States.

Delta-8-THC is found in small amounts in cannabis, but it can be extracted and synthesised from hemp. It is increasingly being marketed as medical marijuana, with less of the high and less of the anxiety that this high can cause. Delta-8-THC, like the other compounds discussed here, is an intoxicating cannabinoid, but it produces only a fraction of the high that THC does, as well as less anxiety and paranoia. It is thought by users to relieve many of the same symptoms that cannabis can, making it a potentially appealing medicine for people who do not want to experience the high associated with cannabis. It is thought to be particularly effective for nausea and appetite stimulation. There is some evidence (albeit from a small study of ten children) that delta-8-THC may be an effective option for preventing vomiting during cancer chemotherapy treatments. While the claims for delta-8 are enticing, there are no good human studies to back up its efficacy or safety, so we must take marketing claims with a grain of salt. There is no regulation of production, and some adverse effects and unintentional poisonings have been reported.